Putting the meat on the bones. Part 1

I was born. I was married. I have had three children. I’m not dead yet (obviously) but if I was, those few details of my history don’t actually tell you a great deal about me. Of course, the generation of 2071 will be able to find out where I lived in 1971; in 2091 they could see what I was doing for work in 1991, and in 2111 they might discover that I wasn’t very well in 2011 and didn’t work that year. But they still won’t know me; what makes me laugh, what makes me angry or what I enjoy doing, or maybe what my weaknesses are, what adventures, tragedies, or triumphs I experienced. We can see the census 100 years after its completion and each release gives us a little more information than the previous one. The census really is a wonderful window into the household of our ancestors, and I love to regularly read through those I have of my people, but the family histories we seek to research and discover should be so much more than a name, a handful of dates and a few occupations. For many it is impossible, but the time spent trying to find those extra nuggets is worth it for those rare details you will discover.

All genealogists envy those aristocrats whose ancestors’ antics and behaviours are so well documented, or those people who descend from people of notoriety, or people who invented things or made noteworthy discoveries. Most of us however, if we look in the right places, will find more than dates of birth and death if we are patient, methodical and persistent.

Some of my discoveries have introduced me to a moment, or a few moments, in a life that has really added a little colour to the hitherto available monochromatic story. It has made me hear some of their words and understand some of their experiences; it transforms the names and dates into real people with beating hearts and air in their lungs.

The most obvious of sources in this quest are old newspapers. Archive libraries close to the geographic area of your interest would hold local papers most likely to have your ancestors in and that would of course involve a great deal of speculative searching. Thankfully one of the best things around at the moment is the British Newspaper Archive, a searchable online repository containing millions of newspapers. It is not by any means complete and you should not rely on it to provide you with a complete story, but it is a fantastically useful tool.

Read on to discover a few things I have learned about my relatives.

William Orme

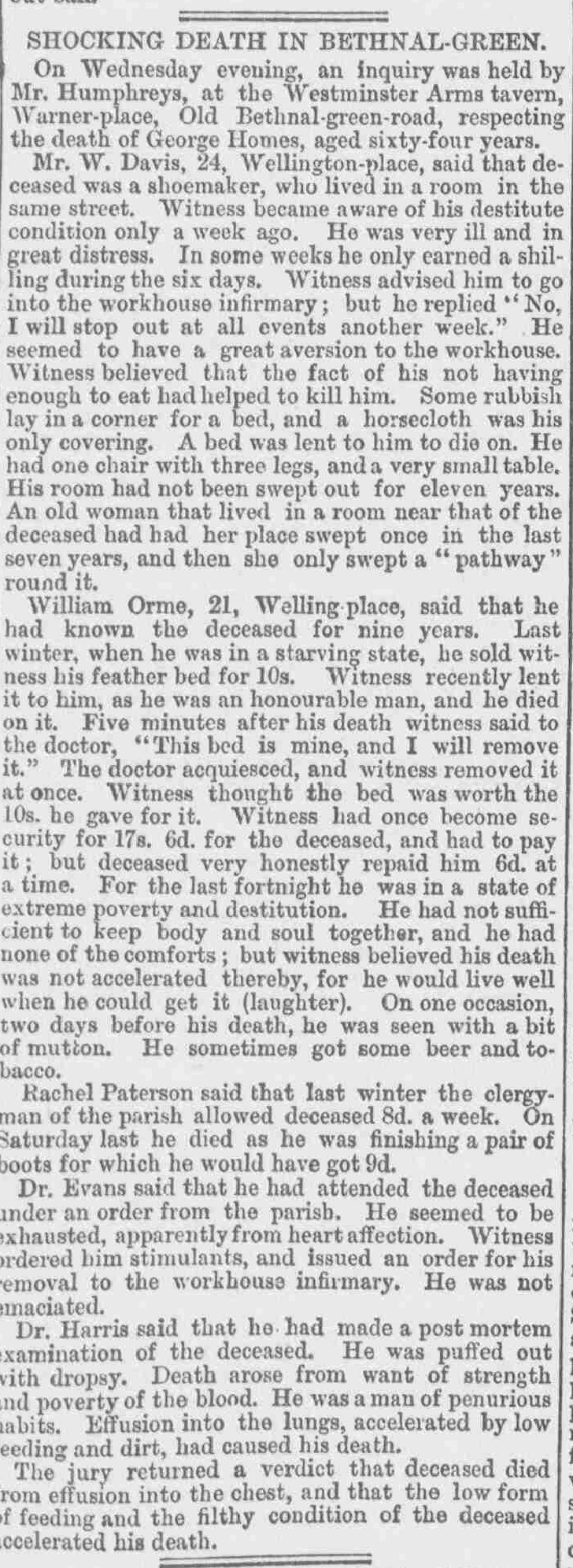

My Great Great Great Grandfather William Orme was born in 1818. I had found very little about him outside of the census returns which gave me an idea of his scraping a living often as an umbrella maker. He lived in Bethnal Green, London, and it took me years to find his death due to a transcription error. Eventually I found that he died in 1893 in Bethnal Green Workhouse. He lived in various roads in Bethnal Green and in 1861 had a ‘marine store shop’ in Wellington Place. A ‘marine store’ in the East End of London seems a strange thing, but it was essentially a junk store, a shop for buying and selling, and was often on the edge of criminality in a ‘handling’ way. Certainly that’s how Dickens portrayed the owners of such establishments in A Christmas Carol and David Copperfield. So that gave me a little idea about old William Orme.

The fact that, like so many East Enders and a good few of my ancestors, he ended in the workhouse emphasised his poverty and lack of any kind of financial stability. It was, however, a very small but priceless newspaper article that I found that really put the meat on his bones for me and provided a minute but invaluable insight into his life, and perhaps even outlook. William Orme had grown up in the East End of London during a time of some of the worst abject poverty that this country’s history has seen. He survived the ’hungry forties’ and he seemed to have remained in employment. He started off as a ‘cane dresser’ and progressed to a fully fledged ‘umbrella maker’, with the brief interlude as a marine store dealer. One of my next jobs is to try and research exactly what being an umbrella maker in Bethnal green in the mid 19th Century entailed as that is another way of discovering how their days were filled. Those days were long too, and there is no better source than Dickens for the trials and tribulations of London workers. There is also a fantastic book that has been like a tangible link to my ancestors of London and that is The Victorian City: Everyday Lives in Dickens’ London by Judith Flanders. (I have a hard copy and a Kindle copy it’s that good). Flanders has cobbled together so many old sources and references and really paints a visible picture of the life of our London ancestors. I thoroughly recommend it, and I certainly read from it often. I love it. While this wonderful book demonstrates to me what it was like for people like my relatives, it does not give me that tangible link to my actual people. That’s where I have had results in the newspapers.

William Orme is surprisingly not an uncommon name in London at the time, and indeed there were several in each generation of my Orme line for several generations, let alone outside of my family. ‘William Orme’ was ubiquitous when it came to searching through newspaper records, as many many names are. After trawling through, patiently and methodically; those useful competencies of all genealogists; I was suddenly awoken from my searching trance at the sight of the word ‘Wellington’. William had lived in Wellington Place, Bethnal Green at the time of my Great Great Grandfather’s birth. This had to be him and upon further scrutiny I was satisfied it was. It even gave his house number 21 in reference to him. The paper was dated 1863, William was 45 years old and together with his wife Sarah he’d had three of his five children by then. The article was wonderful and gave me so much, in so little, of a seemingly insignificant poor man of his times; it introduced me to his poverty, his humour, his generosity and self-preservation.

William Orme is surprisingly not an uncommon name in London at the time, and indeed there were several in each generation of my Orme line for several generations, let alone outside of my family. ‘William Orme’ was ubiquitous when it came to searching through newspaper records, as many many names are. After trawling through, patiently and methodically; those useful competencies of all genealogists; I was suddenly awoken from my searching trance at the sight of the word ‘Wellington’. William had lived in Wellington Place, Bethnal Green at the time of my Great Great Grandfather’s birth. This had to be him and upon further scrutiny I was satisfied it was. It even gave his house number 21 in reference to him. The paper was dated 1863, William was 45 years old and together with his wife Sarah he’d had three of his five children by then. The article was wonderful and gave me so much, in so little, of a seemingly insignificant poor man of his times; it introduced me to his poverty, his humour, his generosity and self-preservation.

Hopefully you can read the article to the above; it is a great read. If it is not clear, write in the comments below and I’ll write out a transcript.

This is an amazing picture of poverty and apathy to it. You can read into the comments of the individuals, the normality of the situation. It is true that official reporting lacked much empathy as a whole, reporting was far from emotionally intelligent, but the dark dismal destitution shines brightly in the description. We today would find the removal of the bed from beneath the body not yet cold appalling, and yet my relative did just that. But these were poor times, times for the living; the dead were gone and in no need anymore. It may have been the case of fearing that had he not seized back the bed there and then someone else would take it sooner anyway. This poor man had not swept his house for ten years, a neighbouring woman not for seven years, and then only to make access; what then I wonder was the state of my family’s house. Probably only a little better. These were days when there were no refuse collection and rubbish languished in large dust heaps in the streets. Judith Flanders’ book explains that so vividly.

Wellington Place does not exist in Bethnal Green anymore. In fact, none of the houses of my family who lived there exists, much cleared in modernisation to make way for tower blocks and much destroyed by the Luftwaffe. But I can work out the geographical space it held and I like that. The Church he baptised my Great Great Grandfather in was a stone’s throw away, and is miraculously still there. This newspaper article gave me a that little bit of flesh on the life of this probably skinny man, who ultimately himself died in the workhouse, but without whose struggle through life, I would never have existed.

Thomas Munt

My Great Great Great Great Grandfather was called Thomas Peter Munt. He was a copper plate printer – a relatively modern job in the early Victorian years. He lived in that same period of poverty, though his start was a little better. His father Peter Munt was a dyer and scourer who lived for over fifty years in Fenchurch Street, London, now of course the heart of the financial world. Peter paid taxes and thrived in the times of pre-mechanised cleaner air of the city. Thomas later moved to the poorer area around St Pancras, had children before he got married and may possibly have been a little disappointing to his father in that respect. Peter had married in the great and still standing and relevant St Martins in the Fields church in 1799.

The census returns giving Thomas’s addresses, his progression from engraver to copper plate printer, and also the late marriage despite children, all gave me a bit of a picture, but again, an event in his life that was documented in a newspaper gave me just that little bit more. In the middle of the night Thomas was walking along Tottenham Court Road looking shifty and got himself arrested leading to the story in The London Standard of January 23rd 1843:

Thomas Munt, a decently-dressed middle-aged mechanic was brought up for re-examination, charged with robbing his employer, Mr McQueen, and engraver residing in Tottenham Court Road, of 3,500 copper-plate engravings and 2,000 others belonging to some person unknown.

The prints were of different sizes and on various subjects, and such as are usually sold in the shops from half a guinea downwards.

The facts of the case are these; On the night of last Tuesday week, Police Sergeant Archer, being on duty in Gray’s Inn Lane, observed the prisoner carrying a large bundle. His timid manner when approaching the officer induced the latter to stop and question him there upon the prisoner seemed much alarmed, and said he was carrying prints, which were given to him by his master, Mr McQueen, to his lodgings in Fenchurch Street. Being further interrogated, he prevaricated so much that the Sergeant took him to the Station-house. On inquiry at Mr McQueen’s, it was ascertained that the prisoner had been discharged from his service about eight months ago; that the prints were his, and had been stolen from his establishment. There were 3,500 in the parcel found on the prisoner. At his lodgings were found 2,000 more, but Mr McQueen could not identify them as his property.

The defence set up by Mr Wooler was that his client had been a faithful servant to Mr McQueen during 20 years, and had taken the prints according to a custom, which allowed each workman to take a copy of the print he executed.

Mr McQueen, however, denied that any such custom was sanctioned by or existed in the trade.

Mr Combe remarked that in the parcels before him there were, in many instances, six or seven copies of the same print, and recommended the case to be sent for trial.

Mr Wooller requested of the magistrate to accept bail but Mr Coombe said the case was much too clear and too gross a one to admit of it.

The prisoner was committed for trial.

Well, not withstanding my blood-line loyalty to my Greatx4 Grandfather, he sounds to me as guilty as the proverbial sin. Also not withstanding his tendency toward a little theft albeit possibly within a worker’s custom where he thought he had a ‘right’, the article shows me other things about his character and activities. He was skulking around Tottenham Court Road with over a thousand prints, going where, I wonder. His nervousness on the approach to the police officer, and his prevarication are all indicators of character too (or guilt) and welcome inclusions to the report for a genealogist.

I searched for the result of the trial in the newspaper and was unable to actually find them (but will keep trying). The outcome was important for me and yet my existence is evidence to me of only one likely and surprising outcome. Luckily for me the trial was held in the central Criminal Court, The Old Bailey, and is documented in another great source for our erstwhile villainous ancestors, “The Old Bailey Online”. I know at this point from the newspaper article that he wasn’t given bail, so from the time of the initial hearing to the trial, for one week, Thomas was in prison.

The Old Bailey records took me through the trial. It gave the two counts of theft Thomas was charged with, one from his long-time employer William Henry McQueen, and one from his more recent employer Joshua Butters Bacon, who incidentally was involved in the printing of the first penny black stamps. Thomas doesn’t seem to have taken the stand, or is certainly not quoted, so unlike William Orme I don’t get to hear his actual words, however it is worth putting the words of the two injured parties here. They, both long-time employers, seem to have learnt something of the customs of their workers by this trial…

WILLIAM HENRY MCQUEEN . I am a copperplate printer. The prisoner had been employed by me for nearly fourteen years—he has always borne the character of an honest man—he had left my service eight or nine months—in working impressions, there are certain copies that are spoiled—the impressions that the prisoner is charged with stealing are of that number—I told the Magistrate I was disinclined to prosecute him—I have since heard that they are generally supposed to be prints which the men suppose they are entitled to—I find such an opinion generally entertained, though, as a master, I never tolerated such a custom.

JOSHUA BUTTERS BACON . The prisoner was in my employ for eight months—a short time since Sergeant Archer called, showed me some print, and asked if I knew them—I said yes, they were my property and my partner’s—I picked out a hundred and odd, which were mine—these are them—they are a great many of the damaged prints—I did not authorise the prisoner in any way to take any—I have been in the trade twenty years, and never heard till last Saturday night that there was an understanding in the trade that the men may take these first impressions. There are three here which I can swear to as mine, and were never given out of my possession to any one—they are worth 3d.,scarcely of any value—there may be seven-eighths of the others spoiled—I believe we employ more men than any in the trade—these are from annuals—when we are printing we throw aside those that are in any way defective—the plate belongs to the trustees of Charles Heath—in the present case I am required to print a certain number—all that are defective we throw aside—those which only require a slight touch, and would have been sent in as good impressions, and paid for, the orders have been completed—each of the partners have a proof, which is an agreement between us and the customers—the prisoner has been in my employ three times—the last time for eight months—the plate has not been in use for some years.

This gives me further information about my ancestor, like the amount of times he worked for Bacon, a well-documented printer of the time, and also that he ‘had always borne the character of an honest man’. That was good to hear in the light of the evidence which in my opinion still pointed towards a guilty verdict in the strict terms of the theft law. Luckily for me however, he was found ‘not guilty’. Lucky for me, because his daughter from whom I descend had not yet been born, and had he been found guilty the likelihood was, like the fate of the defendant after him, that he would be transported to Australia, and that daughter, and subsequently I, would not have been born.

Thomas’s father Peter, in addition to his day job, was a night watchman, prior to the emergence of the Metropolitan Police, and he appears in several Old Bailey trials as a witness. I do wonder if he proffered some kind of influence upon any of the decision makers in his son’s trial.

Thomas was working as a copper plate printer again in the 1851 census, though unfortunately I can’t tell for who, but the recording and reporting of the arrest and trial certainly gave me a better view of his character. He died in 1852 at the age of 51.

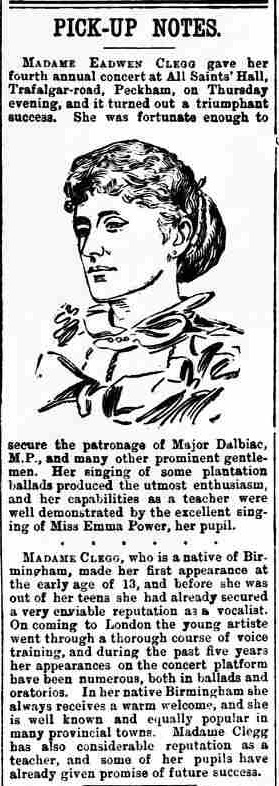

Elizabeth Clegg

One final newspaper report I’m going to show today features my Great Grandmother Elizabeth Clegg, who sang in and around South London under the name Madame Eadwen Clegg. I actually found many reports of concerts she played, and lessons she advertised. Prior to this I’d known of her singing through my patient cousin (once removed) who remembered fearing her loud screechy voice as a child. (I say patient because she suffers so gracefully my non-ending emails asking about her relatives.) This report from 1896 is a somewhat kinder review and I’m sure she would be very pleased that it is being read 122 years later. The sketch holds a likeness of sorts too.

One final newspaper report I’m going to show today features my Great Grandmother Elizabeth Clegg, who sang in and around South London under the name Madame Eadwen Clegg. I actually found many reports of concerts she played, and lessons she advertised. Prior to this I’d known of her singing through my patient cousin (once removed) who remembered fearing her loud screechy voice as a child. (I say patient because she suffers so gracefully my non-ending emails asking about her relatives.) This report from 1896 is a somewhat kinder review and I’m sure she would be very pleased that it is being read 122 years later. The sketch holds a likeness of sorts too.

This is just one way of adding to the story and providing greater perspective on the lives we research. In the next blog in my ‘Putting the Flesh on the bones’ series, I will write about how some of the wills I have come across have also added a bit of personality.

Would love to hear your comments on this and other articles of mine.

Cheers,

Neil 12/4/18