Lionel Clegg: a short life

I am publishing this a hundred years to the day that my Grandmother’s brother Lionel Clegg was killed while serving in the Tank Corps in the First World War. There are some repetitions to stories on my other blogs, but here, it is just about him and his short life. He was 20 when he died despite his gravestone saying he was 21. There is a family who exist because of his death and a family who continued in spite of it. This is those nearly twenty one years.

Lionel Clegg was born on 17th September 1897, in the family home of 410 Old Kent Road Camberwell.

His parents were Samuel Clegg a Yorkshire man who worked as an insurance manager, and Elizabeth Clegg who was from Birmingham, and well known in the area for her social activities. His brother Gilbert was already 11 years old, and his sisters Violet and Dorothy also lived at the address. Sisters Lillian and Florence, and brothers, Tom and James were born over the following few years.

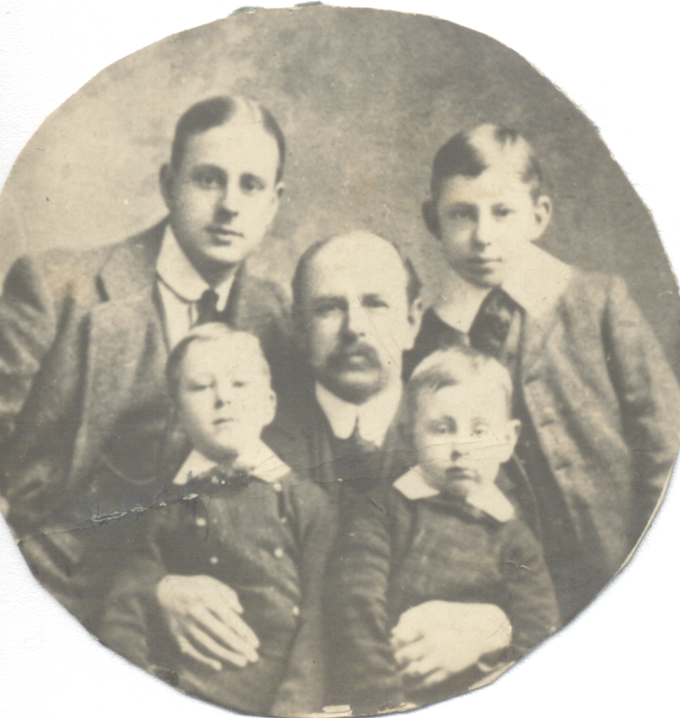

The photo to the left would have been taken around 1907. Samuel is obviously to the centre and Gilbert on the top left and Lionel on the right. The younger boys are Jim and Tom.

Lionel went to nearby Friern School during which the family moved to Peckham Rye. They seem to have been fairly affluent and the house was of a good size and they had a servant living in (census). Samuel seemed to have had his fingers in a few pies, and was a trustee of the Camberwell, Peckham and Dulwich Conservative club, and for three years was a member of the Camberwell Borough Council, as well as being prominent in Masonic circles. Although he worked in insurance he had little foresight in terms of his own family’s financial situation and when he died in 1932 (of cirrhosis of the liver) he had no insurance policies of his own, and so Liz spent the next twenty years, living off the charity of her family.

In 1909 Violet married. The below photograph being taken in the Clegg’s back garden. Lionel is at the front on the right.

Lillian (my grandmother) is in the centre at the front. Sadly three people shown in this photograph were to die in First World War. Lionel, the groom Henry Giles, and the chap centre back.

The war as we know broke out in 1914, and everything changed. Gilbert became an officer in the army. Lionel, having been a clerk in the Insurance company (Liverpool and Victoria) waited to be 18 then joined the navy as an Able Seaman.

He applied for a commission in the navy and not getting it getting it applied to transfer on commission to the army.

He applied for the Army commission on 17th March 1916 showing his preference to be in the infantry; this being of course less than four months before the biggest loss of British military history in one day at the battle of the Somme. I wonder if he would have made such a request had that tragic tactical blunder had been made first, and maybe he would have survived the war staying in the navy. I wonder also what part the family played in pushing him into believing that he ought to be an officer rather than ‘one of the men’. Maybe they thought he would be safer as an officer.

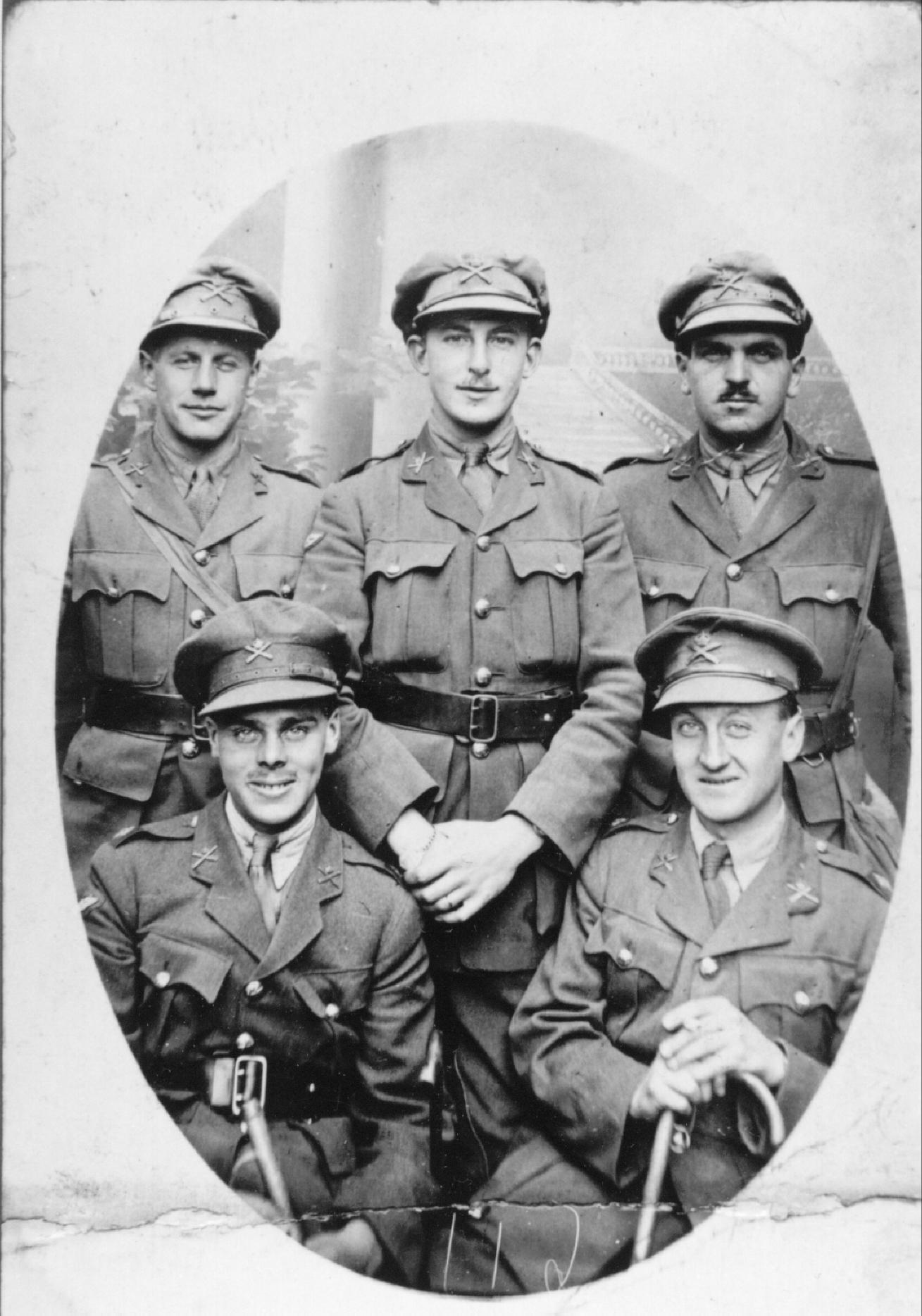

He started his Officer training in Gailes Ayreshire on 5th October 1916, and then was transferred to the Machine Gun Corps (Heavy) in Pirbright on 4th December 1916 for further training. This photograph right, would have been taken not long after that, as it shows him with the badge of the Machine gun corps.

You can see also just about that he has the beginning of a moustache, and I should imagine that took him at this point of his life a little while to grow. He was made 2/Lieutenent.

On 6th August 1917 Lionel embarked at Folkestone to Boulogne and on 25th September he was posted to G Battalion of the Tank Corps and ‘sent to field’. From this period he was on active service and he would have seen a fair amount of action. He was present in the battle of Cambrai. G Battalion were well used in that battle. Lionel’s tank however broke down on route to his rally point and he probably didn’t get into the thick of the battle. This battle was the first time that Army commanders realised tanks for their worth, and also their credibility amongst ordinary soldiers suddenly improved. It was also the first time in history a tank on tank fire fight took place. Lionel still would have taken witnessed some bloody goings on during this time and I often wonder how he communicated this home, and whether or not any wrote any letters about the experience.

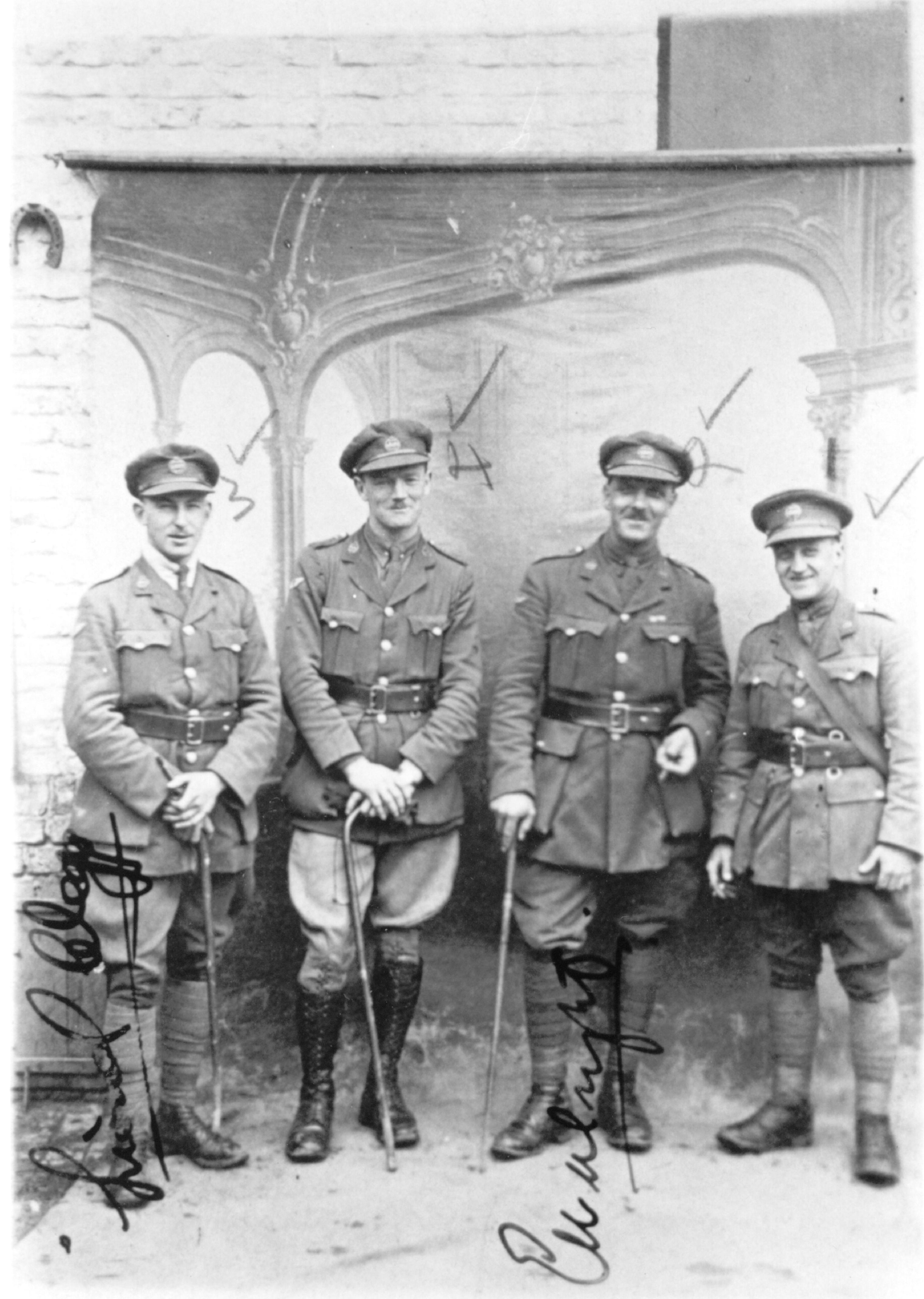

This photograph shows him already looking a little older than his 20 years. His moustache is a little more pronounced, and he is smoking a pipe. On the back of this photograph is written ‘survivors of Cambrai’. The other chap to sign the picture was Captain Wright, who was to be wounded on the day Lionel died. Interestingly the battle of Cambrai took place in November 1917. On this photograph, Lionel wears a wedding ring, and so it is possible this was taken in July 1918.

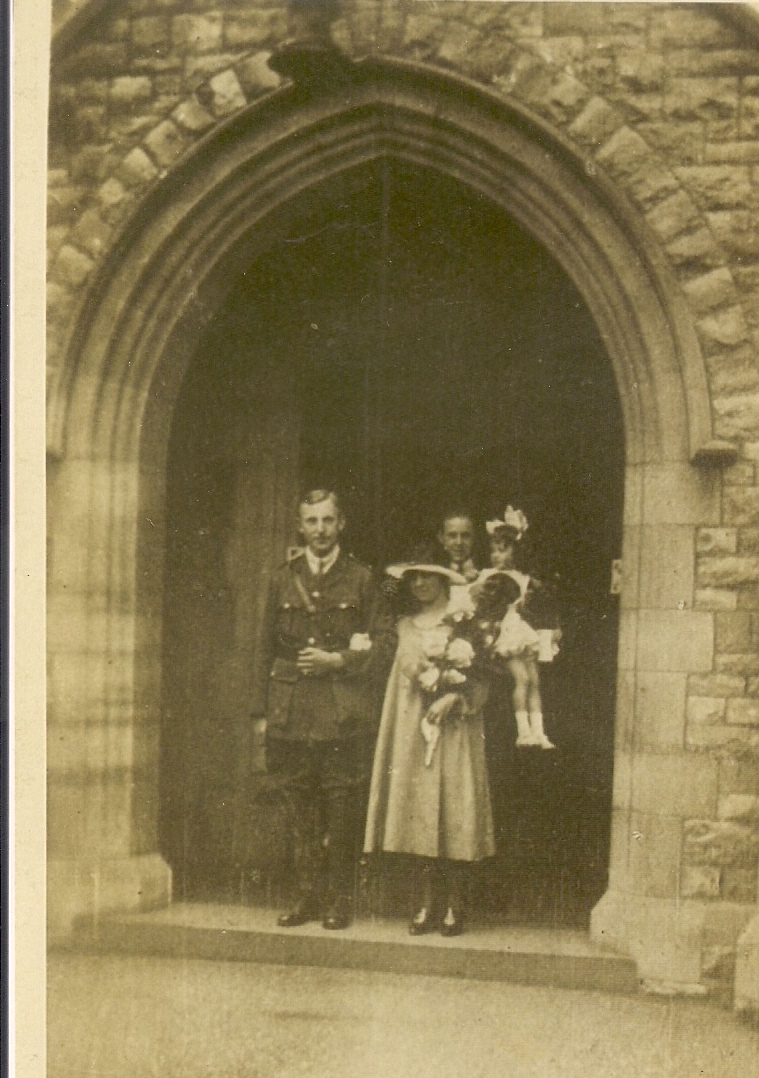

On 3rd June 1918, Lionel returned home on leave. I wonder if during this first week of leave was when he proposed to marry Doris, and that arrangements were made hastily. He certainly applied for an extension of his leave, which was granted on 11th June, the day they married in Silas Church  Nunhead.

Nunhead.

On Tuesday 11th June 1918 the marriage between 2/Lt Lionel Clegg and Doris Fowler took place and was reported as follows in the local newspaper:-…….. ‘PECKHAM HERO WEDS When Second Lieut. Lionel Clegg of the Tank Corps and second son of Mr and Mrs Clegg of Radcliffe House Peckham Rye was recently home on leave from France, he seized the opportunity take unto himself a wife; his wife being Miss Doris Fowler third and youngest daughter of Mr and Mrs Fowler, of Ivydale Road Waverley Park. The ceremony took place at St. Silas Church with the Rev J H Hinchecliffe officiating. The bridesmaid was pretty little Kathleen Giles, the five year old grand daughter of Mr and Mrs Clegg whose father had made the supreme sacrifice last year. The best man was Mr James Clegg, brother of the bridegroom, and another brother Lieut. G S Clegg gave away the bride in the absence of her father . Over 40 guests were entertained at the bride’s house and later the happy couple-they are both not yet 21-left for a brief honeymoon at Bognor. The bridegroom returned to France on Friday last. He went through the grim struggles at Cambrai and brought his Tank and crew safely back. ‘

The whole leave period must have been a blur for him but also for his new wife Doris, but no doubt there were a couple of days of real rest and recuperation in Bognor. It would be their last time together, by Saturday 22nd June Lionel was back in France.

Fighting continued in and around the areas Lionel and G Battalion were posted. There was a huge counter offensive by the German Army on August 8th in which the Tank Corps played no small part at repelling.

Whilst I was in the Bovington Tank Museum undertaking research on Lionel ( in 1999), and trying to find photographs, I was given a book to look at, as it was written by a chap in the Tank Corps, and gave a good insight of life in a tank during this period. I opened the book randomly, and immediately saw the word ‘Clegg’ written and soon realised I had just found (or maybe been shown) an eyewitness account of his death. To describe these events I am best quoting from parts of the book. The book is called The Tank In Action and was written by DG Browne who was at this time a reconnaissance officer in G Battalion (by now referred to as 7th Battalion). Lionel was a Tank Commander of No. 2 Section A company under the command of Captain EV Wright MC.

The 7th Battalion was primarily interested in Bucquoy and Ablainzeville. …… ‘A’ Company were to capture Ablainzeville which they did so easily and with little opposition. The book says ‘One machine gun had kept firing from a ruined house until a tank drove over it…and then proceedings had degenerated into a hunt for souvenirs..’

The night referred to was 21st into the 22nd of August 1918. Lionel’s section of three tanks went toward Aitchet-le-petit, taking out a few machine gun placements in Logeast wood, and then travelled the road between Aitchet-le-petit and Bucquoy, rallying in a small copse half way between the two. They settled there for the night as a battle continued for Aitchet-Le-Grand. The book continues….. “ It was extremely cold that night for August. Jukes and I were huddled together in a bay of the trench when the Major roused us a 3am. He had become anxious about Wright’s section in the copse beside the road, and wished Jukes to walk across and bring the tanks intothe Nissen huts, with the others before dawn…..The copse when we got to it proved to be no more than a triangle of tattered hedge enclosing half a dozen small trees. There were now six tanks in it: including three of A Company, Wadeson’s, Clegg’s, and another). …Having woken them up we hurried them on because he Eastern sky was brightening, and it takes some time uncamouflage a tank, stow everything and start up a cold engine. The crews were sleepy and chilled, and half an hour passed before the first tank was underway. Clegg’s tank and the one commanded by an NCO, went off with Jukes….”.(the road then came under a deluge of shelling)…..” The shells followed us with the same uncanny accuracy and were crashing among the huts hen we reached there. As we turned from the road I met Wright the section commander, stumbling about, half blinded by blood from a wound to his head. I took his arm and ran him down the road to the trench, and judged from the brisk way he stepped out that he was not very badly hurt. Hurrying back, I called in the crews. It was not the moment to keep them out in the open camouflaging tanks, which could be done later. As it was, I was too late. Poor Clegg, having after all come safely through the journey, was the first in and was standing behind his tank helping his crew to cover it with corrugated iron from a hut, when a shell burst at his feet and killed him instantly. The whole thing was a striking example of bad luck. The tanks could not have been seen in that half light, and the bombardment was a mere speculation, aimed, I imagine, at the trenches we occupied east of bucquoy”

Lionel is on the left of the above picture, and the chap sat down on the right is Capt Wright. Sat down on the left is Wadeson who was referred to in the above account. Wadeson went on to win a Military Cross (as Wright , and Waine show off too in this picture), on Sept 30th 1918, when he tried to rescue a tank crew after their tank had been fired upon; during this struggle he was gassed and shot at but survived. Several officers were killed after Lionel despite how close the end of the war was. This is largely because of the important role the Tank Corps in bringing the war to a close. The majority of tank action was in the last two years of the war. The chap in the middle sat down was a South African called Bevil D’Urban-Rudd. He went on to win gold medal at the Antwerp Olympics for 400 metres in 1920, and again demonstrates the sadness of Lionel’s death, and how much of a future some of these young men lost. My First blog on this site tells the whole story of the men on this picture. Read it here

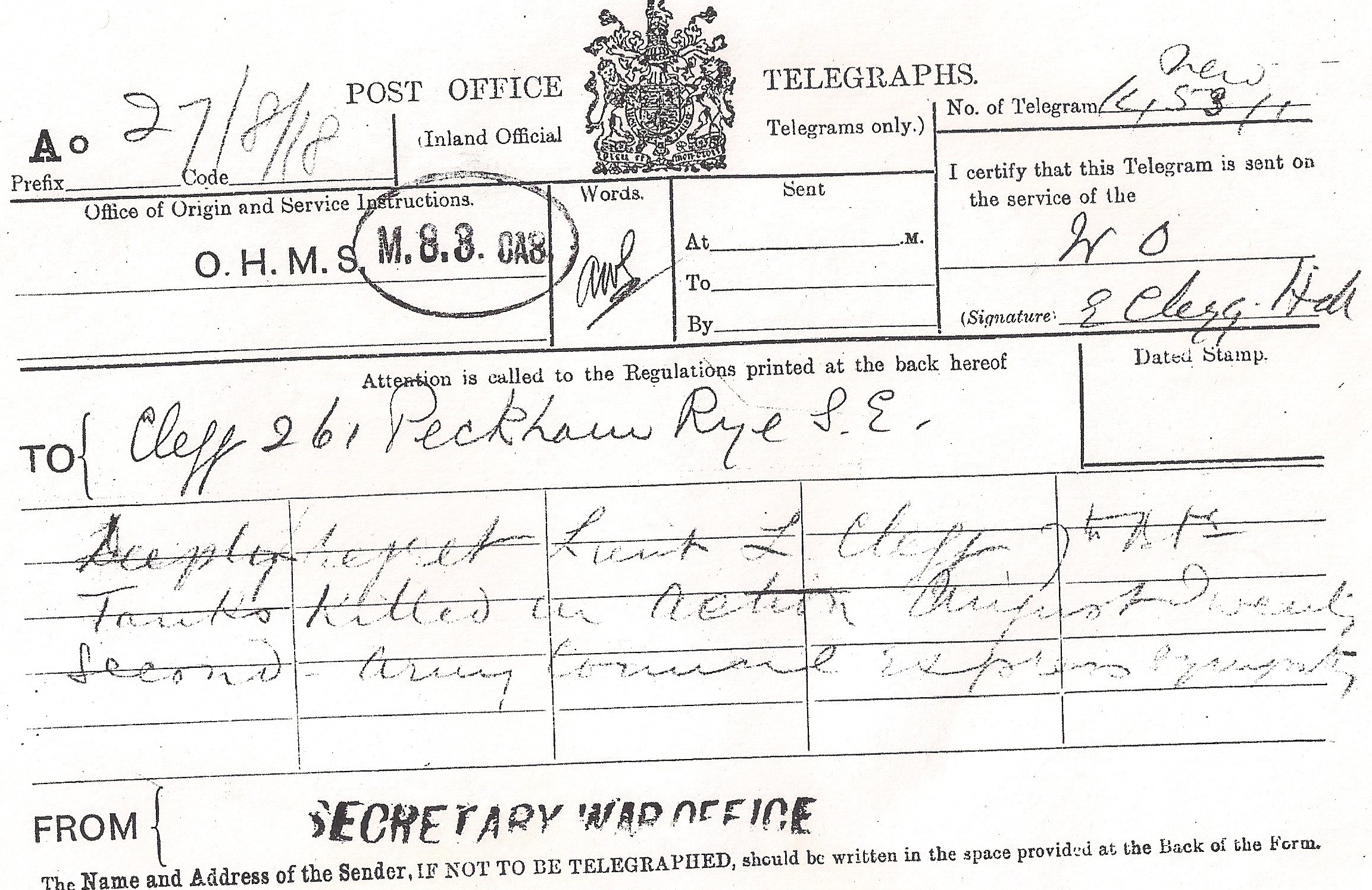

The telegram was sent to Lionel’s parents address because so little time had passed since his marriage that the records were not up to date. The telegram was received 27th August. It simply said ‘ Deeply regret Lt L Clegg 7th btn Tanks killed in action August twenty second army council express sympathy’. It was signed by his mother Elizabeth.

On 9th September 1918 Lionel’s effects were returned to his father. A series of letters were exchanged between the Army office and Doris before she was accepted as his next of kin and she then received the monies owing to him. The effects which were returned to Samuel tell a story in themselves. They include german cigarettes and a German Prayer book as well as his own photographs and letters. I wonder what happened to those things.

On 4th October 1918 Doris received a letter from the War Office informing her that Lionel was buried 500 yards South Eastof Bucquoy, and that it was marked with a durable wooden cross. On 25th June 1920 she received further communication stating that following an agreement with the French government, to remove all scattered graves and small cemeteries, it had been necessary to exhume the bodies buried in certain areas, and that Lionel’s body had therefore been removed and re-buried in Gommecourt no.2 Cemetery Hebuterne. The gravestone which stands there now, has the added inscription ‘In loving memory my dearly beloved husband’. I don’t know if Doris ever visited the grave but I feel she did. I have visited Lionel’s grave four times and will do again!

Lionel’s brother Gilbert survived the war, and all his siblings lived a varied and colourful life.

Doris married again in 1926, and from that union began a whole new family; people who probably would not have existed had Lionel not died. Her second marriage did not survive, and she was reliant on Lionel’s war pension, for much of her life, and thought of him all her life. She died in her late 80s.

Neil

22nd August 2018