The Life and Times of Charles Thomas Orme and Harriett Harrison.

Introduction

I can trace my family’s ‘ Orme’ descendents without doubt to 1818, with some certainty to the early 1700s, and with some probability to the 1600s.

Harriett Harrison can be traced via her mother Harriet Butfoy, further still, again with certainty to the mid 1600s and some probability to the late 1500s in to Belgium and France.

Our family of Orme certainly are in the East End of London for as long as they can be seen in the pages of recorded documentation, and those leading to Harriet can be followed from their moment of liberation from the religious persecution in Europe, to settling in the Bethnal Green area. As it still is now the Bethnal Green area was a haven for immigrants.

Charles Orme and Harriett Harrison are one set of my great great grandparents. I never knew them obviously, but they are me and I am them. Everything about them was East London; their DNA was steeped in the land upon which they lived and their ancestors, my ancestors crowd the cemeteries; even their children didn’t stray far. They were Victorians and though London had barely 3 million occupants they experienced poverty and overcrowding. It was everywhere. The generation of their parents were the subjects characterised and satirised in many of Dickens’ novels; Dickens walked through their areas night after night and observed their ways, sounds and habits, and described their lives so well.

With such limitations to the amount we can learn about one working class, struggling family of the East End and in order to make as full an assessment of their lives as possible, it is important to look too at the generation before and after; the generation that influenced them and the one they passed that on to. This story concentrates on Charles and Harriett but talks about three generations.

Like all of us they were all of their times; no welfare state, little credible health care access, poor communications; beer cleaner than water, and the fog of the industrial revolution building up a dense and acrid momentum. Classism and social injustice was rife and only with the tragedy of the first world war did that begin to improve. Whilst neither Charles or Harriet would live long enough to witness the catastrophe that was unleashed by that, their contribution was as great as any a family.

What follows, therefore is a factual account from records still available of the life, times, and London of Charles and Harriet Orme, my Great Great Granparents. It follows their lives and those of their parents and children. It follows them from house to house and child to child. It shows their occupations, hints at their poverty, and makes no judgement. It doesn’t show what they did in the long evenings, (though the appearance of thirteen children gives an indication of that) or what made them laugh, or who got on with who and who didn’t; with a fact based narrative there is little to base emotional assessments upon. Only occasionally do we get an insight into a character or personality or a real opportunity to comment upon what emotions must have been felt when hardship was all that was known. I have tried not to place a twenty first century view of the conditions they lived in. It was all they knew. This is all I know.

Bethnal Green

To understand the people, the make-up of the place in which they lived must be understood. the following accounts and figures I have edited from a number of publications and contemporary reports so I do not claim to have discovered this from detailed research of my own, but it sets the scene.

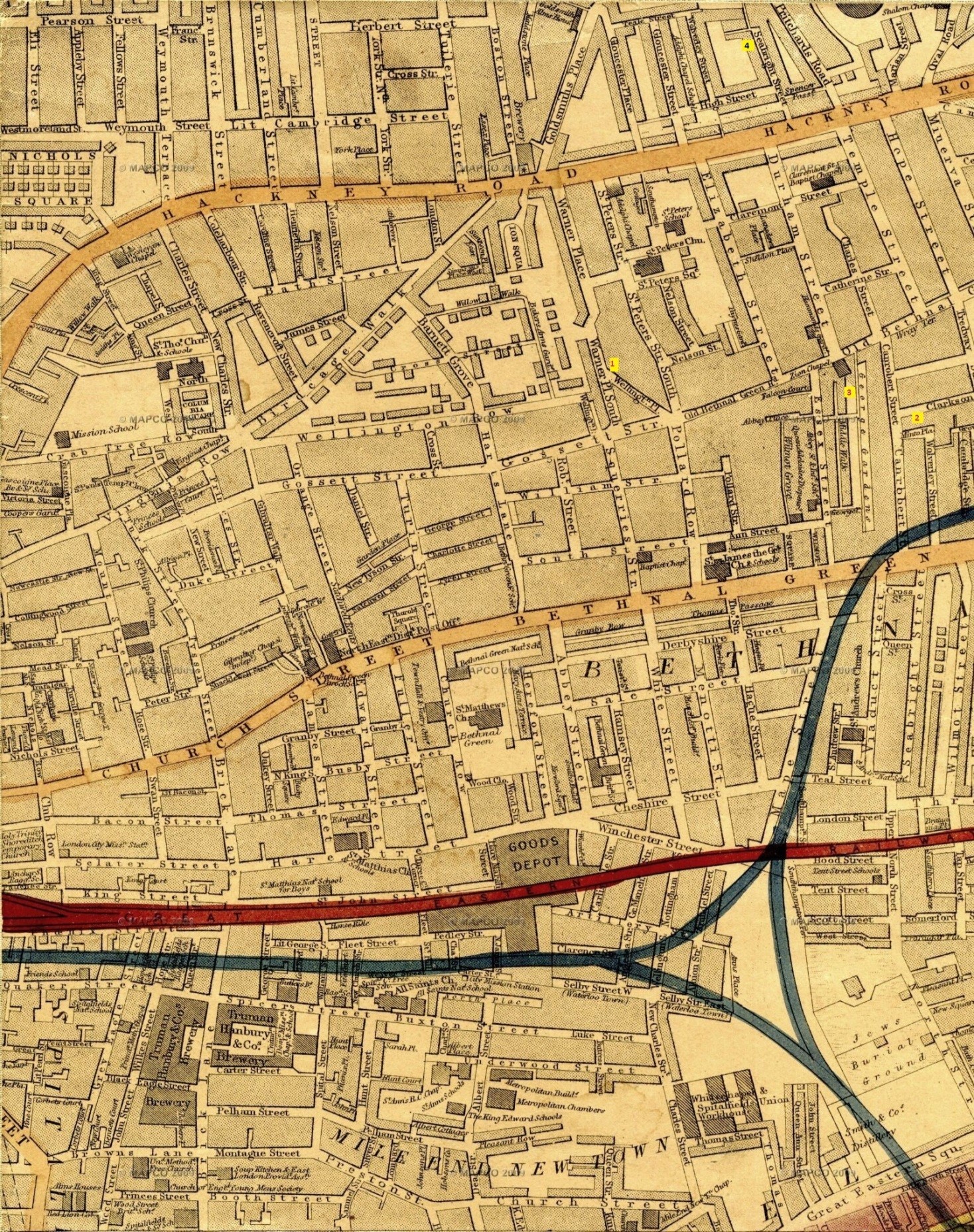

Bethnal green was known as the scene of the legend of the Blind Beggar and later as the classic East End slum; poverty always being synonimous to it’s name. Bethnal Green was about 2½ miles (4 km) north-east of St. Paul’s Cathedral. A hamlet of Stepney until 1743, when it became a separate parish, it was bordered by Shoreditch on the west and north, Hackney on the north, Stratford-at-Bow on the east, and Mile End and Spitalfields on the south. The course of a family history obviously is no respecter of Parish boarders and the story takes in all of those locations.

Between 1795 and 1845 100 acres of formally garden land found in the parish was given up mostly to building or by degeneration into land used as rubbish dumps or by squatters. Bethnal Green lost its attraction for Londoners and as the local weavers grew poorer, gardening plots were abandoned and the summer houses converted into insanitary dwellings. In 1848 the worst sites were Weatherhead’s and Greengate gardens off Hackney Road and Gale’s Gardens west of Cambridge Road, while George and Camden gardens nearby were deteriorating rapidly. (George Gardens features in our story). Many social reports of the 1800s talk about the huge dust heaps, and complete lack of sanitation, clean water, drainage or sewage. Many houses were literally surrounded by the rubbish and effluent of their neighbours. There was no where for it to go and it stayed where it landed.

Several industries were located in Bethnal Green because of its proximity to the London markets, the available labour, and the convenience of the nearby canal transport. Much of the raw materials and subsequently completed goods, however, were carted or taken by hand to warehouses and middlemen there or in neighbouring districts. The dominant industry for nearly two centuries was silk weaving. Traditionally attributed to the French and Flemish Huguenot influx into Spitalfields after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, it actually originated earlier. Weavers were recorded in Bethnal Green from 1604 and silk-weavers from 1612, the earliest at Bishop’s Hall. They were present in the western parts, in Collier’s Row, Stepney Rents, Cock Lane, and Brick Lane by the 1640s. By 1684 it was said of Bethnal Green that ‘the people for the most part consist of weavers’.

When the main incursion of Huguenot silkweavers arrived, the English masters welcomed cheap, skilled labourers during a time of demand for French fashion. The immigrants’ skill in figured silk, brocades, and lustrings brought a boom to the industry in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Silkweaving then was small-scale and paternalistic with masters and journeymen usually working in the master’s house, itself set among the smaller journeymen’s houses.

Another long lasting related industry was dyeing. A dyehouse stood on the east side of George Street near St. John Street, probably by 1694 and lasted until Ham’s Alley was built between 1783 and 1791. Spitalfields and Shoreditch mirrored these trades too. Another of my ancestors Peter Munt was a successful dyer in Fenchurch street in the late 1700s an dearly 1800s.

In the East End approximately 68 per cent of adult males were employed in clothing (59 per cent in silk) in 1770 and only 48 per cent (39 per cent in silk) in 1813. The repeal of the Spitalfields Acts in 1824, which led to a steady drop in wages, and the treaty of 1860, which opened English markets to French silk, accelerated the decline, as did fashion’s favouring other fabrics over silk and the spread of cheap factory production elsewhere, notably in the north of England.

Factories employed only a minority of the workforce. Large numbers affected by the decline of silkweaving in the 1820s and 1830s were absorbed into home- or workshop-based industries. The chief manufactures, lacking the monopoly position of silk, were furniture, clothing, and shoemaking.

The cabinet makers, chairmakers, and upholsterers industry then developed rapidly, making cheap furniture with imported timber which from 1820 could be brought by the Regent’s canal to the North of Margaret Street which became Whiston Street. Although cabinet and chair makers were the most numerous, there were many specialists to make other articles of furniture, frames, or boxes, besides carvers, workers in cane, ivory, bone, willow or veneer, and upholsterers, japanners, and french polishers. The industry was small-scale, in homes or workshops. By 1872 nearly 700 addresses in Bethnal Green were connected with the industry, compared with 85 in Hackney and 659 in Shoreditch.

There were at least three saw mills and 16 timber yards in the early 1870s, of which 8 yards were in Bethnal Green Road and 4 in Gosset Street. Saw mills were built in 1873 in Sewardstone Road and next to the railway at Cambridge Heath and in 1874 in Busby Street. Numbers in the industry reached 4,326 in 1881 and 4,766 c. 1890, more than half of them described as cabinet makers and upholsterers. Although Curtain Road in Shoreditch was the centre of the trade, Gosset Street was the manufacturing centre. When the Nichol slum came to be cleared in 1890, its occupiers included 120 cabinet makers, 74 chair makers, and 24 woodcutters and sawyers. The small workshop remained the standard unit of production, with yards and saw mills interspersed. Mills often let space and steam power to up to 20 specialist workers. Increasing mechanization brought cheaper products, carvers for example being replaced by machine mouldings. A tendency towards larger premises gave rise to three with more than 100 employees by c. 1900, but individuals continued to make and hawk single items.

The intense competition and existence of many small workshops which eluded inspection, encouraged sweating, which was exacerbated by Jewish immigration. In 1888 Brick Lane was notorious for boy labour, many garret masters worked people until 11.30 p.m., and a larger factory near Bethnal Green Junction station, with 60-70 employees, worked them until 10.0 p.m.

Housing remained a difficulty throughout the 1800s for the poor. Acts to alleviate housing conditions were still largely ignored. The medical officer explained in 1867 that the Public Health Act of 1866 was unworkable because of high rents, scarcity of employment, and new taxes which had forced tenants to let out lodgings and thereby increased overcrowding. The Torrens Act of 1868, which provided for the demolition of unfit houses on payment of compensation, similarly threatened more overcrowding. It was usually not enforced, as the medical officer reported in 1883, since vestries were largely composed of landlords. Neighbouring parishes like Hackney, by enforcing the legislation, merely displaced their own poor, who moved into Bethnal Green.

Gibraltar Street Bethnal Green

Gibraltar Street Bethnal Green

Charles Booth’s 1880 poverty map is a great map to follow when looking at Victorian London

Charles Booth’s 1880 poverty map is a great map to follow when looking at Victorian London

Charles Orme’s childhood.

Charles Thomas Orme entered the world on 19th September 1857 in 21 Wellington Place Bethnal Green (1 on the map) He was baptised in St Peter’s Church Bethnal Green the year the Victoria and Albert Museum was opened, and Queen Victoria had formally appointed her husband Albert to be Prince Consort. British forces were fighting in several places in the world, and were at this moment putting down the Indian Mutiny, and recapturing Delhi.

The below picture shows Charles’ Great Great Great Grand daughter Kezia stood in the doorway that baby Charles was taken through for his baptism, 157 years later. One of the few local churches to survive the Blitz.

Wellington Place diagonally joined Old Bethnal Green Road with Warner Place South and only nine years earlier had been described thus:- ‘There is no proper footpath here, the gutter is generally full from the drain at the end being stopped up, and the whole of the public way exceedingly filthy and dirty from that cause, and from being on a lower level than the adjoining street, called James-street; this place is chiefly occupied by weavers ; there is an open space in front of the houses where the public deposit all kinds of refuse and garbage, and create an offensive nuisance.’ (Sanitary Ramblings, Being Sketches and Illustrations of Bethnal Green, by Hector Gavin, 1848)

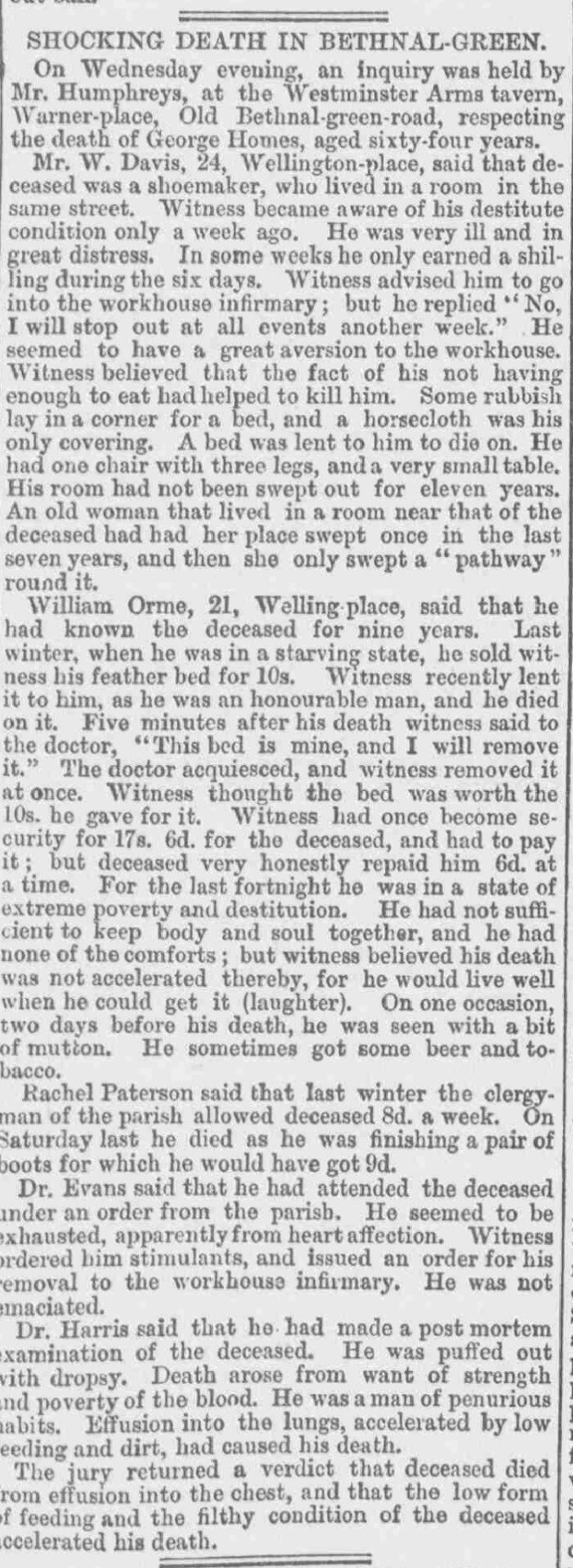

It is difficult to say if no. 21 was one of the newer ones built in 1853 or from an older build as described above. Needless to say, it would not have been the most salacious, and conditions would have been poor and basic. There is no better way to imagine the circumstances and attitudes of this time, than to read something in which those involved in the story can be heard. The William Orme referred to is Charles’ father and we get to hear his words.

The newspaper article above speaks for itself and emphasises the poverty and simplicity of the times. This article was published in the Lloyds Weekly London Newspaper on Wednesday 4th September 1864. In this article we get the only indication we are likely to ever see of the character of William who was at this time 46 years old. The fact that he paid out money against his poor neighbour’s bad debt, that he made a comical remark during the formal process, and also that his own circumstances were such that he needed to ensure that he immediately retained a bed that a very smelly, filthy man had literally just died on are perhaps indicative of his personality and the dire straits of his own family.

In 1857 Charles was the first child of his 39 Year old father William, and 34 year old Mother Sarah who had married Christmas day the year before in nearby St Jude’s Church Bethnal Green. Neither appear to have been married before, and their marriage certificate shows that neither could read and write, as both signed their names with the mark ‘X’. One of the witnesses at the wedding were Sarah’s brother Philip Sorrill. Sarah and Phillip were the only children from their labourer father Thomas’s first marriage.

William, was born in Shoreditch in 1818, the son of a Dyer and sometimes Weaver, and had himself during the 1850s gone from being a general labourer to an Umbrella Maker. This probably occurred around the time he was living in 1851 in Paternoster Row under the shadow of St Paul’s Cathedral. At this time he lodged in the family of a publican Isaac Woolman. Surrounded by trades people he may have taken the opportunity to find a niche rather than remain a labourer. Only a few doors away lived a Frenchman names Sepman Soloman, who was an umbrella maker, and this may have been his introduction to the trade he would be generally engaged in.

A couple of years after Charles was born, he was joined by a brother, William who was baptised in St Peter’s Bethnal Green on 12th February 1860. The 1861 census shows them living at 22 Wellington Place and that William snr had left umbrella making to try his hand at being a Marine Store Dealer, which he did from their house. Marine Store dealers were essentially dealers in rags. A Marine Store Dealer was a licensed broker who bought and sold used cordage, bunting, rags, timber, metal and other general waste materials. He usually sorted the purchased waste by kind, grade etc. He also repaired and mended sacks etc. It may explain his eagerness to retain the bed referred to in the newspaper article, as it may have been something to sell as opposed to use.

1862 brought a sister for the two young boys, and Emily Mary Ann Orme was baptised in St Peters church on February 16th 1862. This record shows that William had returned to his trade of being an Umbrella maker.

Harriet Caroline Sarah Orme, was born on September the 6th, but six months later the family buried her in Victoria Park Cemetery Hackney.

On July 8th 1867 Sarah, now 45 years old, gave birth to the final sibling Mary Ann Ellen Orme who was baptised in August 25th that year also in St Peters Bethnal Green.

Middle Walk

Between 1867 and 1871 William and Sarah, and their surviving children, Charles, William, Emily and Mary moved to 6 Middle Walk Bethnal Green. This was a spitting distance from their old road. Just twenty years earlier that general area had been described in some instances, as ‘unfit to house cattle in’, and in others as ‘tolerably clean’. ‘They were totally without drainage of any kind, except into shallow cesspools, or holes dug in the gardens and were consequently extremely damp, with the inhabitants suffering much from rheumatism, febrile diseases, diseases of the respiratory and digestive organs, from nervous affections, and cachexia. There is very seldom any water laid on to the houses; one stand-tap, as in Middle-walk, George-gardens, generally supplies five, ten, or sixteen houses. Many houses are altogether without water, and the inhabitants require to get it as they best can. In Wilmot-grove the peculiarity of barrels sunk in the ground is to be remarked. Some of the houses have wells, as in Camden-gardens. Very few of these houses have regular cesspools; the privies are sometimes placed close beside the entrance to the house, at other times at the extremity of the garden bordering the narrow lane or footpath. They are, in the majority of cases, full, in some instances, overflowing, and frequently, like the houses themselves, in a dilapidated condition. Another peculiarity in this district, is the number of alleys and narrow lanes, many of them forming cul-de-sacs. The houses in these alleys are always of the very worst description, and are in an excessively dirty state. There is seldom any house drainage, or if there be, it is only to a gutter in front, where the water stagnates, till the sun’s heat shall cause it to disappear by evaporation. It is the nearly universal custom to throw the refuse water and garbage on the streets.‘

It must be expected in that time, however to have improved somewhat, and certainly all of the four children that William and Sarah took to the address survived to adulthood.

By 1871 Charles had left whatever education he had attended if any, and at the age of 13 was contributing to the household working as an Errand boy.

Living but a few doors away from the Orme’s at no 2 Middle Walk was the Harrison Family. They had also recently moved to this street, and although they were a far younger set of parents, the similar ages of their own four children to that of the Ormes brought the two families close.

Henry Harrison, the father, was at this time in 1871 32 , twenty years junior to William Orme. Henry’s wife was Harriett who was 31. Harriett had been born a Butfoy, and from a line that can be traced directly down the ages in Bethnal Green to Gabriel Boutefoy who came over to London from France,in the 1640s to escape the persecution of the Hugenots. Her father William Butfoy married Charlotte Everett. Charlotte had already had three children who were probably born in Bethnal Green Workhouse as she was living there at the time of their birth. William and Charlotte had two daughters fairly quickly after their marriage including Harriet, and while they were in infancy William had died, leaving Charlotte to try to fend for herself and young children. She had worked and lived as a weaver actually in Weaver Street in Bethnal Green, and at the age of 40 when Harriett was only 4 she must have worked all hours she was able to seek light. Charlotte did not fair well, and within four years was back in the Bethnal Green workhouse where at the age of 44 she died. Her daughters were left in the care of their half- sister Elizabeth Mann. Although that care of course meant they had to work and earn their own bread. All three females worked as silk winders. The weaving industry was still rife in East London.

So Harriett had a very tough beginning to her life, and probably hoped to bring better to her own children. Ending up in Fife’s Court living with her sister, did lead to her to meeting her neighbour Henry Harrison. Henry’s mother herself had now lost two husbands and was bringing up her two generations of children. Henry and Harriett had married in 1857 in St Matthews Bethnal Green. Harriett their first daughter was born in 1858 and Emma was born in 1860. In 1861 however, Emma died and she was buried at Victoria Park cemetery Hackney. In 1860 Henry had been a Parasol maker, and in 1871 he was a cane dresser which was part of the umbrella making process. They had three more children, Ellen, Henry jnr, and after a four year gap in 1867 came George Harrison.

So in 1871 the 13 year olds Charles Thomas Orme, and Harriett Harrison lived with their respective families in Middle Walk Bethnal Green. Their fathers’ were both Umbrella makers and undoubtedly worked together,and both families had experienced the tragedy of child death, so common in this period and disproportionately prevalent in this poor area of London’s East End but no less difficult. Their proximity and parity of experience must have brought the children from both familes very close. Henry and Harriett were the same age, as were their ten year younger siblings Mary Orme and George Harrison. Both sets of friends were to marry.

They would have been aware of the death of Charles Dickens the year before, and may have been aware of the introduction this year by Prime Minister William Gladstone of four bank holidays a year. Harriett’s work as a fringe maker would have left her at home a lot of the time, and though the young errand boy Charles would have been doing deliveries and odd jobs for people certainly over Tower Hamlets, and quite likely all over London, building up with it a good knowledge of his area, and becoming very street wise in the process.

Around this time Harriett’s father, 32 year old Henry, contracted Tuberculosis, one of the major illnesses of the time in that area. The family had moved to Georges Gardens, a few metres away from Middle walk, and an area that had literally evolved from a series of Gardening sheds. There was a chest hospital only twenty years open in Bethnal green, but the nature of tuberculosis was not known until 1882, so there was little hope for Henry. He must have suffered greatly, and visibly deteriorated in front of his young children, before he finally died on 18th November 1874 aged 34, replicating the brief life span of his own father. The informant to the registrar to register the death was his friend and colleague William Orme, who had also been present at the death. Henry’s children were exposed to the same fate he had received, that being the early loss of a father.

Charles grew steadily, learning the ways of the word through his work as an errand boy and during the mid1870s he staring learning what would to become his life’s trade, that of a Gilder. He was a picture frame gilder, and sometimes referred to as a carver, and would no doubt have worked in a nearby small factory which added to Bethnal Greens growing industry of woodwork.

The obvious close relationship between the Harrisons and the Ormes must have been strengthened by the help provided after the death of Henry Harrison. Charles Orme and Harriett Harrison certainly had become very close; three years later having set up home together on 21st February 1877 their first child Harriett Elizabeth was born. Charles and Harriett were living by this time in very close by Wolverley Street and April 1st saw the first of many baptisms of their children in St Judes Church. No record, however, exists for a marriage between the two. This will be explored a little later.

Harriett and Charles moved to Columbia Rd and this was where their next child named after the father was born. Charles Thomas (jnr) was born on September 8th 1879. On 23rd May 1880 Charles admitted young Harriett into the local school.

In 1881 the young family of four were recorded living at 28 Columbia Rd Bethnal Green. Charles’ parents William and Sarah had moved to nearby Minto Place where William was still an Umbrella Maker, but they lived above a ‘Sweetmeat’ shop. Sarah was listed as a laundress, so it is likely they rented a room upstairs from the shop which is listed as a private property, but that they had no business with it. All of William and Sarah’s other surviving children still lived with them, Mary and Emma still being teenagers, and William jnr listed as being a gilder, no doubt working with his brother Charles.

Charles and Harriett continued throughout the 1880s to increase their family and as was generally the case in this time the children came almost every two years. with the woman falling pregnant almost immediately after stopping breast feeding the previous child. Mary Ann Emily Orme was born on January 21st 1882. Later that year on 13th October, Charles’ mother Sarah died in the London Hospital in Whitechapel. The cause of death being given as disease of the Tarsus, and amputation of her foot. This almost certainly would have been as a result of tuberculous; arthritis is an infection of the joints caused by tuberculosis. The joints most frequently involved are the spine, hips, knees, wrists, and ankles. Most cases involve just one joint. The informant on the death certificate is Es Persse who was a doctor at the hospital. It is likely that she died shortly after or during surgery. Little did Charles think at this point that this hospital which five years later would be the home of Joseph Merrick the Elephant Man, would also be the place that where he would also end his days.

Another son, William, named after Charles’ father and brother was born in Sebright Street on November 15th 1883.Wiliam was to become my Great Grandfather. I have his original short birth certificate. On Dec 9th that year he was baptised in St Judes Church Bethnal Green. Ellen Mary Ann (possible named for Charles’ sister Mary Ann Ellen), was born on 4th October 1885 and baptised in St Jude Bethnal Green on 25th that month. They lived briefly at 9 Canrobert Street. Harriet was pregnant again, when in about March 1887 baby Ellen died, and on 6th March the family buried her in an unmarked grave in Manor Park Cemetery Newham. By now the family had made their final collective move to 58 Whiston Street.

Pictured above is St Judes Church Bethnal Green. A huge part of the lives of the Orme family in terms of baptisms, I feel it is unlikely they were regular Sunday visitors. There is no trace of the church now other than a road named after it in the space it left after being destroyed in the Second World War.

Their new home in Whiston Street would be a huge effect on the family, and a place of stability. The last place of stability for Charles and Harriett. Many of their children of would meet their future Spouses in this Road. It is pictured here in the 1970s shortly before being demolished.

The road was just south of and parallel to the Regents Canal, which would undoubtedly played a large part of their growing up. There are numerous accounts of people falling and drowning or being rescued from the canal. One chap called Jackson who lived next door to the Ormes received an award for saving up to 90 people from the canal.

On 4th August 1887 that year their third son, named after Harriet’s father and her brother, Henry George was born. On August 21st Henry was baptised, at St Judes, their preferred church even though they had moved a bit further away. Sarah Alice was born on 13th April 1889.

Harriet’s brother George Harrison had also become a gilder, and most likely worked at the same place as Charles, and his brother William. George lived on Hackney Road, and on November 4th 1889 he married Charles’ sister Mary Ann Ellen in St John’s Church Bethnal Green. The entry shows that George could not write but Mary could. Their story was even more tragic in that five of their nine children died in infancy.

In April 1890 Joseph Merrick the renowned deformed ‘Elephant Man’ died. This would have been widely known as he had become somewhat of a celebrity rather than freak show by then, and certainly was known in popular culture. This would undoubtedly be one of the subjects of conversation along with the growing topic of the fear invoked by the murders of Jack the Ripper, which had started in 1888 in nearby Whitechapel and now were accepted as being part of a series. On 30th November 1890 St Judes was once again visited by the family, there having been the arrival of their 5th Daughter, and 8th child; and 2nd named Ellen after the baby they had lost barely three years earlier.

1891 started with them having seven living children, the eldest 14 years old, and the youngest 3 months. They lived at 58 Whiston Street Bethnal Green. Between 1889 and 1891 they shared the house briefly with the Bastow family but as of the 1891 census they shared the house with the Graves family and so probably only had one floor of what would have consisted of barely three rooms. Not only did they have their children, they also had William, Charles’ 30 year old brother and co-worker with them too, as well as a lodger, a boat maker called Richard Pikeman. In the census all their children are listed as being scholars. It is quite commendable that the elder ones, those 14 and 11 were still at school. They probably could have done with the income, which was no doubt helped with the two lodgers.

In April 1891 young William Orme now 7 years old had joined his elder siblings in Maidstone Street School. Whilst the school day was almost certainly split by gender, he may well have walked there with one of his neighbours. The Morley family, lived at 70 Whiston Road. Their youngest child Elizabeth Emma Morley had was a year older, and started at the school a year earlier than William. Their stories would unite later.

In 1892 Harriet was once again 7 months pregnant when Ellen, not yet 2, died and on 15th February joined her namesake sister in Manor Park Cemetery Newham.

Grace was born that 22nd June and so starkly different to her late sister would live until 1978.

In 1885 briefly prior to their move to Whiston St the family had lived in Canrobert Street, adjacent to which was Minto Place, a small cul-de-sac. Charles’ father William can last be found amongst the documents available from the time living there that year. He certainly wasn’t there the following year. It is difficult to know how his last years were spent, and I’d like to think that Charles gave him support and shelter, though in all reality his umbrella making father was probably not able to earn, and with all the young mouths to feed, together with his brother and another lodger he did not have the room. William appears on the records again in 1893 when on 23rd January he died of bronchitis at the age of 73. He died in the Bethnal Green Workhouse, indicating that he had been unable to earn his way for a while. Many died of chest related illnesses, often not because of smoking, but more likely because of the damp conditions in which they had long lived, and the smog of the city added to that. Having said that 73 was not a bad age to have lived to and certainly seems to have lived a lot longer than his siblings, his father and sadly as we’ll see, his two sons. Charles registered his father’s death with the same registrar who had registered some of his children’s births. The death certificate indicated that Charles was present at the death. It may be that William had not been an inmate at the workhouse long. Life throughout England was tough at this period of history. Though the tide of thinking was changing, and plight of the poor and their welfare was gradually increasing on the Government’s agenda, it was still down to the local parish to look after their poor. If a person, who hitherto had led a comparatively comfortable life became infirm, through disability, age or injury, and their families could not afford to look after them the workhouse was the only option. Often it was the only available medical facility.

William’s own mother had died in the Shoreditch Workhouses in 1853 and that place was substantially less cognitive to human needs than even the Bethnal Green workhouse of 1893 when William died. That still, however would have been pretty dire in our standards today.

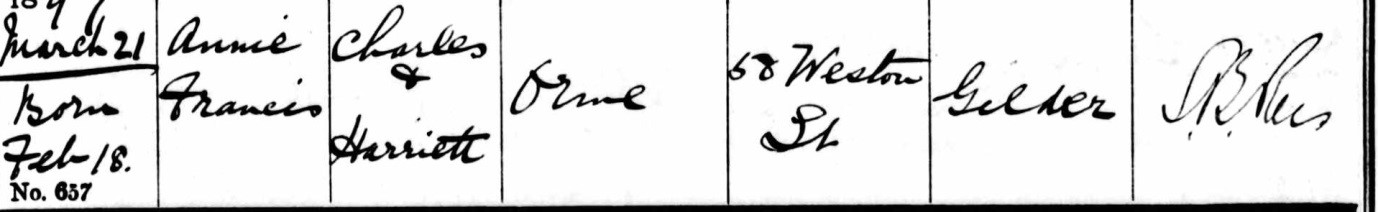

Charles and Harriet had another four children in the 1890s. James was born in November 1893, Charlotte Lillian in September 1895, and Annie Frances in February 1897. James was baptised in their local Haggerston Church St Augustine, and Charlotte back in their more familiar St Judes’ of Bethnal Green. Strangely Annie was baptised in both St Judes in March and St Augustine in July. What’s more I can find no record of a civil registration being made of her birth.

Then on the 18th September 1898 their final child and the third named Ellen, this time with the middle name of Edith was born. On 10th October after 19 years of pregnancies they baptised the last of their children, this time at St Augustine Church Haggerston. It may seem strange today that parents would call children who arrive subsequent to those who died by the same name, but it was very common in the Victorian times, and examples litter our family tree. Charles’ father William had two brothers called Isaac, both of whom died in infancy. This third Ellen, happily lived into adulthood and beyond, she married Albert Duggan in 1929, and can still be seen in the electoral roll of 1964 living in Islington.

In January 1899 William Joseph Morley, a neighbour from 70 Whiston St died aged just 51. He was the father of young William Orme’s future wife Elizabeth Emma Morley and though they wouldn’t marry for another 12 years it is likely that the two families were friendly. William Morley had died of bronchitis and exhaustion just like his father and grandfather, both also in their early 50s at death. He had tried a succession of jobs to keep the bread on the table, and in the 1880s had been a cab driver. This would have been out in all weathers all the time to earn his way. His death certificate described him as a lamp cleaner.

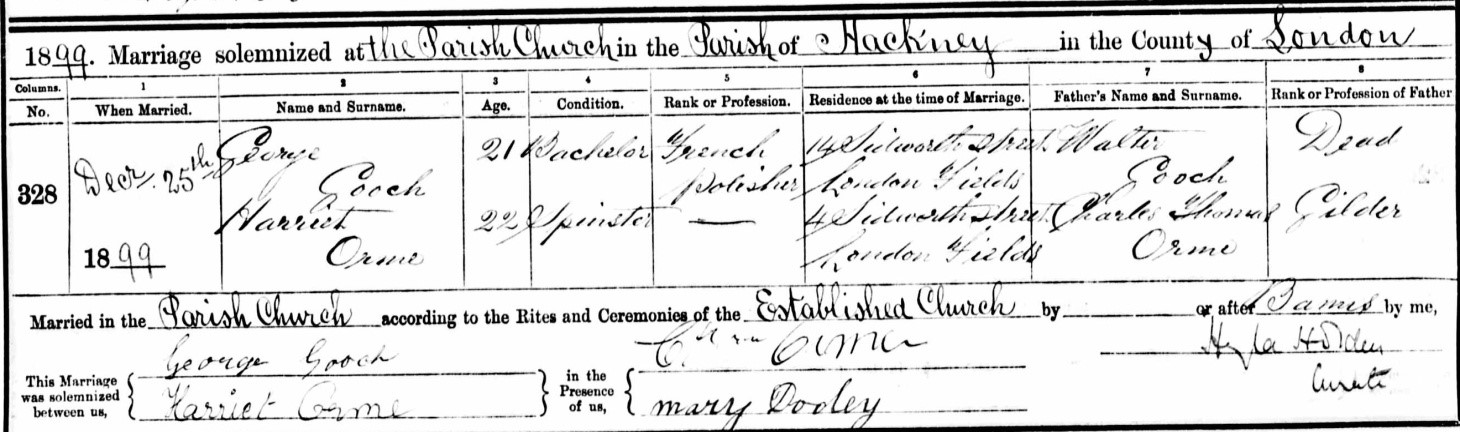

As the 20th century loomed Charles and Harriet were living in their small house with their 12 surviving children the ages of whom ranged from 2 months to 22 years. That last Christmas of the century saw at least one of those children having left the nest and being married. On 25th December 1899 Harriett Elizabeth, their eldest, married George Gooch, a French polisher, in the Parish church of Hackney. One of the witnesses was Charles Orme, though whether it was the bride’s father or brother I can only compare with the brother’s later marriage certificate and seeing that the signature is different, I can only assume that this 1899 signature belongs to their father Charles Thomas Orme snr and is the only example of h is writing (if it is his) that I have found.

is writing (if it is his) that I have found.

20th Century

London began the 20th century as the capital of the world’s largest Empire and Britain’s dominant city. One third of the entire trade of Great Britain passed through London’s docks.

In 1901 Charles and Harriett were 43. I doubt they would have been some of those lining the streets between Victoria and Paddington on February 2nd 1901 as Queen Victoria’s Coffin was carried toward Windsor, though they would of course have been very aware of the events. The Queen had died on 22nd January on The Isle of Wight; on every street corners the newspaper sellers would have been shouting of the event.

Their sons Charles, William, and Henry,were still iving at home, all gilders with their father. Henry was only 14. The 1901 census, actually shows Charles as an employer so it is likely that his boys were working for him. I don’t know to what extent did he own a business, it certainly wasn’t something that brought prosperity to the family. Sarah, Grace, James, Lillian, Frances and Ellen were still young children, and the family, though missing their recently married elder sister, also had living with them Charles’ brother William ,who probably worked with his brother and nephews as he too was a gilder, and also Harriet’s 37 year old brother Henry Harrison who was working as a marble mason. The census showed also that Charles and Harriett had an adopted son living with them. This was Albert Bastow who was 11 years old. Adopting would have been a passing not official term, but his story is worth telling.

The Bastows- A Victorian interlude.

Alfred’s parents, Edward Bastow and Alice Eliza Moore, who had been step siblings for two years following the marriage of his father and her mother, had married in October 1884. They both gave the address of 82 Whiston Street. A year later their first son Edward was born in 66 Whiston Street. Frederick Amos Bastow was born in 1886 and then Albert James Bastow had been born in 22nd September 1889 in Scawfell Street Haggerston.

In 1891 Alfred’s maternal grandmother was living at 80 Whiston St, though he, his two brothers and parents were living in Ipswich Street Acton, where father, Edward ,carried on trade as a butcher.

Something happened in their family life, and 1897 saw their mother Alice living for a short while in Hackney workhouse. Edward and Frederick were living with their father’s brother and at 13 and 15 were working as biscuit packers. The following year 10 year old Albert started at Pritchard street school where his next of kin was registered as his Grandmother Ellen at 82 Whiston Street . He only spent two months there. Two years later in 1900 he was registered in Maidstone Street school and was now listed as living at 58 Whiston Street with Charles and Harriet’s family.

1901 saw Albert being listed as the Ormes’ adopted son. His mother was living with her mother, and his two brothers were living with their father’s brother. What happened to Albert’s father I do not know, for I can find no further trace.

The epilogue to this Bastow’s story is that later in 1901 Frederick died aged 13, their mother died in 1909 aged 44, and Albert who did spend the rest of his life living with the Ormes, died in 1916 aged 26 from tuberculosis, probably too weak and unhealthy to have joined the military. He was buried by the Orme’s in Manor Park Cemetery. His brother Edward lived until 1961.

Back to the Ormes

By 1901 Charles’ son William was by now probably feeling the confinement of the house a little. Not only him, his parents, his seven siblings, but also his father’s brother, his mother’s brother, the recent probably anthropological addition of Albert Bastow, and also a lodger 35 year old gas fitter Henry Ferguson was living there.

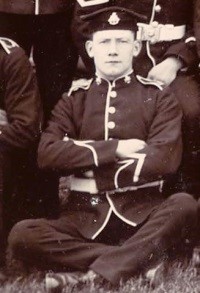

On 31st December 1901 he went to the recruitment office and signed up as a soldier in the Royal Sussex regiment. He was now 18 years and one month old and didn’t need his father to sign for him. He was described as being 5 ft 4 ½ inches weighing 121lbs and with a maximum 34 ½ inch chest expansion. His hair was described as reddish, his eyes grey and his complexion ‘fresh’. He was considered fit for recruitment and signed on for 7 years service with a further 5 on reserve. He became Private 6737 Orme of the Royal Sussex Regt.

He was admonished on 4th March 1902 for returning to Barracks in Curagh drunk. This would have been at the tail end of his training. 1st Battalion The Royal Sussex Regt had been, during this time, engaged in the Second Boer War which had started in 1899 and finished at the end of May 2002. Following William’s initial training he was posted to St Helena Island from 10th May to 25th August 2002. So he had got there just before the war ended and on this Island which of course Napoleon had died at 80 years earlier it now was used to keep prisoners of war from South Africa. From the 26th August to 19th December 1902 William was actually posted to and served in South Africa. This would have been just an occupying force but his presence there earned him the South Africa medal. He was then posted back home where he stayed until June 2004. The photograph here of William, by now nicknamed Mash, was taken at Shorncliffe in 1903.

Meanwhile back in London the Orme household was carrying on living life amidst a changing London, as the relationships between Queen Victoria’s grandchildren started to decline, the apotheosis of which would culminate in the First World War.

Charles and Harriett’s first grandchild Grace Florence Gooch was born on 6th July 1902. Their own youngest Ellen was only 3 at this time of course.

It was during 1903 that Charles first noticed a lump in his groin. This was an Inguinal Hernia. It pushes through a weak spot in the surrounding muscle wall (the abdominal wall) into the inguinal canal, a channel through which blood vessels to the testicles pass in men. Charles sought advice, and was able to push it back in itself. These kind of lumps can occur during heavy lifting or even a particularly difficult cough, or constipation can also bring it on. He was given a truss to wear, which effectively was a strong pair of supporting pants which held the area tightly and kept the lump escaping out from the hernia and carried on with life adjusting slightly to the great pain as and when it came.

Whilst only in his mid to late forties this hernia was the catalyst for Charles to slow down somewhat. The family though, was still dependant upon his wage to survive, even though their own numbers within the walls of 58 Whiston St were starting to come down.

Private William Orme had left already and having had his own adventures in South Africa. In December 1904 of 2nd Battalion The Royal Sussex regiment was midway through a year in Malta when having completed his first three years he signed on to confirm his intent to complete 8 years with the Regt. In May 1905 he was posted to Crete where stayed until May 1907 when the 2nd Batt. “terminated its stay in Crete”, and moved to its new quarters at Belfast for another term of service in Ireland. During its stay in Belfast, the 2nd Battalion had a good deal of unpleasant duty helping the police to quell riots and keeping order during strikes.

On October 21st 1906 Henry George, Charles and Harriett’s youngest son married Annie Victoria Cattanatch who lived at 87 Whiston Street, but had grown up in Pritchard street probably in her father’s pub. Their marriage record said they were 21 but of course Henry was actually only 19 years old. This was the second marriage of the children for Charles and Harriett and their first son- in- law George Gooch performed the role of witness. Henry and Annie quickly brought Charles and Harriet their 2nd Grand Child, Henry William Orme, who was born on 14th March 1907, suggesting a reason for why they married so young with Annie likely having been nearly three months pregnant when they married. Henry George was known as ‘Buff’, almost certainly because of his profession as a French Polisher. Henry William would later become known in the family simply as Young Buff!

The Goochs provided a third Grandchild for Charles and Harriet, George Charles Gooch was born on 9th June 1907.

It is difficult to assess how Charles and Harriett were as grandparents but in 1907 they still had five of their own children aged between 5 and 15 living with them. Their married children didn’t live far and I’d like to think that 58 Whiston Street still was the hub of all their lives.

On August 8th 1907 Charles Thomas jnr, the eldest son and now 27, married 23 year old Margaret Hall in St Andrews Church Bethnal Green. They both listed London Street as their address at this time. Charles was still a Gilder, and probably working with his Dad. This wedding also helped blossom the relationship between young Charles’ sister Mary Ann Emily, and Margaret’s brother James Hall, who in turn married at the same church the following February 9th1908, a Sunday. We can be sure that William, was not at the wedding. He was still serving in the Army and was currently in Belfast where he would have been involved in putting down a number of riots. He was probably aware of the fact that his sister, less than two years older, was going to be married on the 9th. On Saturday 8th February William had gone out on the town in Belfast, and at 10.50 that evening he was found there drunk, and brought back to camp by two Military Policemen L/Cpls Harris and Davis. Although not sentenced until the following Monday, it is highly likely that while Mary and James Hall were being married, and enjoying their day with many of their family present, that William was banged up in the regimental cell sleeping off his hangover, and awaiting his sentence. This came on the Monday when Lt Col Henry Browse Scaith fined him 2/6 and awarded him 8 days confinement.

During the evening of Friday 27th March 1908 Charles left his house in Whiston street, perhaps in a hurry as he had forgotten to put on his truss, despite five years of coping and managing his hernia. He jumped onto a car (almost certainly a horse drawn omnibus or cab of some sort) and felt his hernia burst out. He was in immediate pain. The next day he starting vomiting and couldn’t go to the toilet at all. He went to a doctor who could not replace the large lump that had developed, and for the next few days Charles was in agony, constantly being sick and could not open his bowels. He suffered like this until the Wednesday 1st April when he presented himself to the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel. The very hospital his own mother had died in in 1882.

He was seen by resident and eminent surgeon Mr Furnival. He was a chap who really knew his stuff for the time. He had worked at the hospital since 1899 having been elected surgeon at St Mark’s hospital for Diseases of the Rectum, and having in 1897 received an award for an essay on ‘The pathology, diagnosis, and treatment of the various neoplasms met with in the stomach, small intestine, caecum, and colon’. Charles was therefore in the best of hands, however this was 1908, and even today the situation he was in would be perilous and life threatening. Furnival noted that there was a tight strangulation of the hernia site and that it was bright purple.

On Thursday 2nd April Mr Furnival undertook the surgery. The operation was conducted under general anaesthetic and appeared to have been successful. When Charles came around whilst his pulse was 100 his temperature was normal, and there was no vomiting. On the 3rd it was noted that the wound site was healing well, and again that his temperature was normal, but that still the bowels had not opened. This was not, as it turned out, a good sign. A bad night followed during which his temperature starting rising, and on the 4th he started being sick again. The description of this is particularly nasty as due to his bowels not having opened, the vomit was the bodies escape for that which had not escaped the natural way. His stomach became very painful and abdomen distended. His temperature was 100 and his pulse 106. Vomiting continued and the pain must have only increased. He lasted until the next day and at 3.42pm on Sunday 5th April 1908 Charles Thomas Orme died aged 50 years 6 months. That he died in that particular hospital, the same as his mother, is relevant to the amount of information I have gleaned. All the story leading to his death was available to me from the museum now attached to the London hospital which had his medical notes retained.

The politics of the country followed a similar path as that very weekend the Prime Minister the renowned Liberal and true reformer Henry Campbell-Bannerman resigned due to ill health and became the only prime minister to die in 10 Downing Street 3 weeks later.

On Monday 13th April 1908 the family buried Charles in Manor Park Cemetery Newham. There was no headstone for his grave, and he ultimately shares his space in the ground with a number of other strangers who similarly lacked the funds for their own plot.

Charles had missed an event that he would have seen building up over the last couple of years. Weeks after his death London hosted the 1908 Olympics at White City; it had originally been supposed to be held by Italy but following the Versuvius eruption in 1906 their budget for the Olympics was put to relief ends instead.

At the time of Charles death three of his children were expecting grandchildren he would never meet. Harriet Gooch was now pregnant with her third child Albert Ernest Gooch who arrived 30th September and Margaret, Charles’ ( jnr) wife, was pregnant with their first child Valentine who was subsequently born on 5th May 1908. Mary Ann, now married to Margaret’s brother James Hall, was also expecting their first child Ivy Maud who was born later that same year. William, still serving in Belfast, with the suddenness of his father’s death, would have been unlikely to get back in time for the funeral.

Harriet Orme now a widow, was able to remain at 58 Whiston Street while some of her children remained and helped the income, for a while, though was becoming unwell herself.

At the end of 1909 William left the army and returned to the East End. He was declared fit and placed on the reserve. Upon leaving the army William was 26 years old, and now 5ft 6inches, and he left to be a gilder and was to live at his old address of 58 Whiston Rd. It is likely he didn’t stay there long. In 1911 he lives with his brother Charles Thomas, an his family in the pub e ran in Pritchard Street, the Kings Arms. William worked there as a barman.

By the time of the 1911 census 54 year old Harriet had moved, probably unable to afford the Whiston Street rent, to 11 New Street London Fields Hackney. Living with her was 22 year old Sarah, 19 year old Grace, 17 year old James who was now a butcher, 15 year old Lilly, 14 year old Annie,12 year old Ellen, and of course 21 year old Alfred Bastow, her adopted son.

Henry (Buff) and wife Annie, had moved all the way next door to 56 Whiston Street with 4 year old Henry and 1 year old George.

A short time later in June of 1911 Harriett became reliant upon the parish for her health care and she found herself living in Hackney Workhouse. But having only recently moved to Hackney from Whiston Road which had been for some while in the parish of Shoreditch, Hackney applied to Shoreditch for her removal to their care rather than staying at Hackney.

She certainly stayed in Hackney Workhouse for at least ten days before it was established that Hackney was not responsible for her upkeep. It is not clear if she was able to go home after that stay of she spent a while in Shoreditch workhouse. It may well be that she only stayed there for free hospital attention as the records of hackney show her staying in the Infirmary. She was suffering from an incipient valvular disease of the aorta. The entry in the book, shown below however answered one huge question and posed others.

Within the description of her situation it says that she has no sons, when as we know she had 17 year old James, as well as Charles and William living not far away around the corner. It may be that they weren’t able or prepared to pay to help out or in fact that she didn’t want them to be burdened by the Parish.

Additionally it clears up another huge issue. Written on the document is the date and place of her marriage to Charles. It states that they married at St Judes which is where most of their children were baptised, but the date states 13.8.1874. There is no record in the civil records of their marriage, and this date allowed me to specifically check the church records. There was no marriage in St Judes on that date, and having searched right through St Judes records I have found no record of their marriage. The only conclusion to draw from this is that they never actually were married, and that the date given here was made up for the form. It may be they just never got around to it in the early days and said they were at the first birth, and then never did anything about it.

On April 7th 1912 William married Elizabeth Emma Morley. They are my great grandparents. They had known each other for years having grown up together in Whiston street, and attended the same schools. They were married at St Michael and All Angels church Hackney, and the witnesses were William’s sister Sarah, and Elizabeth’s Brother William. Elizabeth’s parents were William Joseph Morley and his wife Sarah Ann nee Munt who had married in 1869 in St Clements Danes, whilst living in Wych Street, a bit of a den of iniquity at the time. They subsequently lived at 70 Whiston Street with her widowed mother Sarah.. Sarah’s father had been a Copper plate printer who was aquitted of theft of hundreds of prints in 1843 in the Old Bailey though that belongs to a different story.

A month later on 13th May 1912 James Orme left Bethnal Green for a life in the Royal Navy. Harriet remained living at 11 New Street which was most likely rented to her daughter Sarah.

In April 1913 Harriett, still only 53 years old and living in New Street London Fieldswith daughter Sarah, became quite ill. She still suffered with valvular disease of the aorta and became now stricken with dropsy. On 18th July she died. Her children buried her in the same cemetery as her husband, but unfortunately were not able to secure the same plot and she was also buried in an unmarked grave on 22nd July 1913 in Newham Cemetery. It seems likely her children knew her death was imminent. Harriet’s daughter Harriet who had her own children and lived several streets away was present at the death of her mother, and registered the event that same day.

Epilogue

Whilst Harriet and Charles had both now gone, their contribution to the world was immense. Of their four sons three fought in the First World War, one badly wounded and one killed. Many people now descend from Harriett and Charles, living across the world. Sadly I have never been able to find a photograph of them, and that remains a constant quest. It is unlikely there is one but I keep trying.

Here is what happened to their children as much as I can glean.

Harriet Elizabeth Orme had married George Gooch in 1899. They had four children and Harriet died in 1954 aged 77.

Charles Thomas Orme the namesake of his father, had married Margaret Hall in 1907. They had two children Valentine and Elizabeth. On 26th August 1914 as the world decended into the Great War the 34 year old Charles signed up with the 3rd Battalion Middlesex Regiment telling them he was 27 years old. He started his training in Rochester. While there in Nov 1914 his 1 year old daughter Elizabeth died. On December 27th he failed to turn up to tattoo and was fined 8 days pay. He may well have been out drinking that evening, and that may well have been one of his last occasions in which he was able to. On 29th December 1914 his Battalion were sent to join the British Expeditionary Force in France.

On 29th December 1914 his Battalion were sent to join the British Expeditionary Force in France. On 3rd February he was in Reninghelst and the next two days in the embattled shell that was Ypres.

On 6th February the Middlesex Regt went to the Front line just south of Ypres and stayed there until they were relieved overnight on 10/11th February. During that time they had occupied very bad conditioned trenches, largely due to the incessant artillery fire aimed upon them. They lost in those days 1 officer and 26 other ranks killed and 2 officers and 56 men wounded. 80% percent of the men suffered from Frostbite. On 12th February they then returned to relieve the East Surreys. On 14th the Germans attacked their trenches and they lost ‘O’ Trench. Captain Hilton was killed and Lt Col Stephenson organised further available men at battalion HQ (28) to counter attack. In that afternoon men from the East Surreys and a party from 3rd battalion Middlesex which included Charles, tried to retake O Trench. Lt Ash was killed along with practically all the men. The total losses between the 12-15 February was 4 Officers Killed, 3 wounded, 44 other ranks killed and 62 wounded and 156 missing. Such was the violence of the battle, the bodies of those known to have died as well as those missing were not recovered sufficiently to allow for later identified burials. Those men still have no known grave and their names are engraved in the Menin Gate in Ypres as a memorial to them. Charles hadn’t had to join up. His two brothers had, and this is what probably motivated him to. He was 36 and been in Belgium barely a month and a half when he was killed. He received the War Medal, the Victory Medal and the 1915 Star posthumously which was delivered to his widow Margaret.

We visited the Menin Gate a hundred years to the day after he was killed, and have done so every year since.

Mary Ann Emily Orme as we have seen married James Hall in 1908 shortly before the death of her father. James was the brother of Margaret, Charles’s wife. They had a daughter Ivy Maude Louise Hall who had been born late 1908. James Hall was 5 ft 7” with brown hair and brown eyes and a tattoo of a sailor and an American Flag on his right arm and some ‘defective’ teeth. He was a chauffeur and mechanic and joined the Army Service Corps in September 1914. In July 1915 he was posted to France and in January 1916 he saw two children drowning in the Bethune Canal. Despite the freezing temperatures, he dived into the water and rescued them. He spent half an hour in the icy water, and then another 3 and half hours in the cold wet clothes. A month later he started getting pain in his back and in the October he was admitted into hospital with a number of painful symptoms which collectively were diagnosed as Albuminuria. He was shipped back to England and spent several months in hospital before being medically discharged from the Army. I can’t be sure without buying several certificates what happened subsequently to James and Mary Ann.

William Orme, left the army in 1909. In 1911 he was working for his brother behind the bar in the Kings Arms Pritchard street, and then returned to his former trade as a gilder. In 1912 he married Elizabeth Emma Morley with whom had gone to school so many years earlier. They had three children the first of whom was William Charles Orme born on April 8th 1913.

Being as he was still part of the Army Reserve he was mobilised in August 1914 and returned to Army life this time in the 3rd Battalion Royal Sussex. 3rd Battallion were a depot and training Unit and consequently he wasn’t sent away and was involved in training, being made Lance Corporal in April 1916. In February 1918 William was transferred to the 1st battalion Royal West Kents who were in Italy where he spent a largely event free few months, to be discharged finally from the army at the end of 1918.

William later worked in a printing works. Elizabeth died in 1957 and William lived alone in his flat in Burntoak cooking well for himself. He was a through and through Londoner, loved his pint of guiness at any and every opportunity, and later in life was one of those characters stood outside the tube station selling the Evening Standard. He died in 1964 two years short of meeting me his Great Grandson.

Henry George Orme had been known simply as ‘Buff’. In 1911 he had moved his family all the way to 56 Whiston Street, next door to the home in which he grew up.

Henry with some of his sisters. L-R Back Row, Annie Francis, Charlotte, Ellen, Sarah. Front Row L-R Grace, Henry (Buff), and Harriett.

Henry and his wife Annie had nine children and Henry died in 1964 aged 77 having been a widower for five years.

Sarah Alice Orme married just two months after the death of her mother in September 1913. She married Alfred William Gooch, the younger brother of her sister Harriett’s husband.

Grace Orme, married Joseph George Bennett in April 1915. He was an engineer and they both were living in 11 New Street Hackney which definitely superseded the Whiston Street address as the central place for much of the family. Their wedding was witnessed by two of the Gooch boys George and Albert and also Lilly Orme.

Joseph and Grace moved to Hampshire. They had two children Gladys and Norman. Joseph died in Aldershot in 1966 and grace died there in 1978 aged 85.

James Orme was the youngest son of Charles and Harriet. He started his working life as a butcher before maybe realising the physical work that that entailed. (As did the author of this chronology). In May 1912 at 18 ½ years old James signed up into the Royal Navy. He signed up for 12 years. James at this time was 5ft 4 ½ inches with a 36 inch chest and ‘J.O’ tattooed on his right forearm.  He became a Stoker and by Summer 1914 he was serving aboard HMS Laertes. This ship, along with many others was involved in the first naval battle of The great War, the battle of Heligoland-Blight. In this battle James was badly injured on 28th August 1914 when the ship was hit by four shells from the German Ship Mainz. He was then ashore probably in hospital until the end of April 1915, when he returned to a restored HMS Laertes.

He became a Stoker and by Summer 1914 he was serving aboard HMS Laertes. This ship, along with many others was involved in the first naval battle of The great War, the battle of Heligoland-Blight. In this battle James was badly injured on 28th August 1914 when the ship was hit by four shells from the German Ship Mainz. He was then ashore probably in hospital until the end of April 1915, when he returned to a restored HMS Laertes.

James secured a brief period of Leave in 1917 when on September 16th he married Lilian Ann Eatten.

He then returned to HMS Gibralter, a depot ship in the Shetland Islands. He stayed on in the navy to honour his 12 year contract and left the Navy in July 1924. James and Lilian had one son Eric. James died in April 1953 when they lived in Second Avenue Walthemstow, aged only 59 years old. I have not purchased his death certificate to see if his war injury contributed to his death. Lilian lived until 1966.

Charlotte Lilly Orme at some stage changed her name to Charlotte Lydia Orme, and that was the name she married when in 1919 she married George Samuel Batt. George Bennett her brother in law was one of the witnesses. They had no children and George Batt died in 1934, leaving Charlotte / Lydia on her own until she died in 1966.

Annie Frances Orme; she who was baptised twice but seems to have not been registered. Well certainly not under her baptised name anyway and I can’t find any realistic alternatives either. Anyway, she married Frederick James Gowen in 1924. They had no children and died within three months of each other in 1975.

Charles Thomas Orme and Harriett Harrison, lived to 50 and 53 respectfully. They produced 13 children, 11 of whom lived to adulthood, and they nurtured the son of an even poorer family. They worked and they endured. My grandad who was the grandson of Charles, though never met him, alluded to the fact that Charles was a drinker and would go missing for a few days shortly after pay day, but there is no real evidence or indication of a neglectful way about him. Maybe he liked to escape every now and again, but with his lot in Victorian London, perhaps who wouldn’t. I think they were salt of the earth and I love that I am able to write so much about a couple who were never going to set a world on fire, but who’s DNA now runs free and far across the world.

Neil.

Sept 2019